What is the prostate and where is it?

The prostate is a small gland, about the size of a walnut, which lies just below the bladder. The tube draining the bladder, called the urethra, passes through the center of the gland, to the penis.

Valve mechanisms, also called sphincters, maintain continence and stop urine leaking out of the bladder. They are located just above and below the prostate gland. The one above, is incorporated into the bladder tissues. The one below, the sphincter, tends to be more important.

What does the prostate do?

The prostate gland is a part of the male reproductive system. It develops at puberty and continues to enlarge throughout life.

The prostate acts rather like a junction box. It allows the tubes that transport sperm from each testicle and the tubes that drain from the seminal vesicles to meet and then empty their contents into the urethra. The seminal vesicles consistent of two pouches that provide nutrients for the sperm and lie immediately behind the prostate.

At the point of orgasm , sperm, seminal vesicle fluid and prostatic secretions enter the urethra and mix together, forming semen. This is then ejaculated out through the penis by rhythmic muscular contractions.

What controls the prostate gland?

The growth of the prostate is controlled by testoserone, the male sex hormone. Most testosterone is made by the testicles, although a small amount is also made by the adrenal glands, which lie on top of each kidney. The hormone goes into the bloodstream and finds its way to the prostate. Here, it is changed into dihydro-testosterone (DHT), a more active form that stimulates growth of the gland. The prostate gradually enlarges with ageing, resulting in symptoms such as reduced urine flow and a feeling of incomplete emptying of the bladder having passed urine. This enlargement is usually benign (non-cancerous).

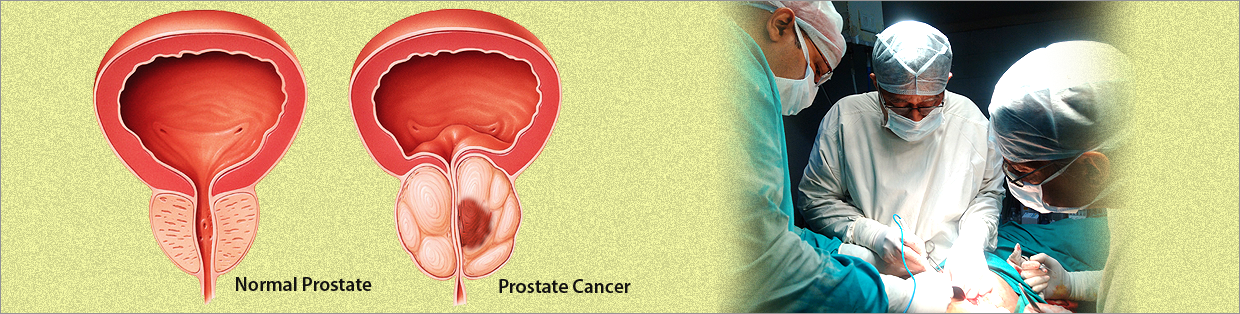

What is prostate cancer?

Normally in the prostate, as in the rest of the body, there is a continuous turnover of cells, with new ones replacing old, dying ones. In a cancer, the balance between the new and old cells is lost, with many more new ones being made and older cells living longer, as the process of planned cell death has been disrupted. The malignant growths are known as prostate cancer. They differ from benign enlargements in that the cancerous cells can spread ( metastasise ) to other areas in the body. However, sometimes the cancer can be detected before it has spread outside the prostate.

How does prostate cancer spread?

Cancer cell can spread by directly growing outwards through the capsule of the gland into the neighbouring parts of the body, such as the seminal vesicles or bladder. The may occasionally spread through the bloodstream and implant and grow in the bones of the spine. Finally, cells can spread through lymph vessels. These vessels are like a second system of veins, except that, instead of blood, they contain a milky fluid that is made up of the cell's waste products. Lymph vessels drain via lymph nodes (special bean-shaped filters), to finally empty back into the blood circulation. Thus, the lymph nodes can also become invaded by cancerous cells as they try and tidy things up.

How common is prostate cancer?

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancer in males, affecting many thousands of men. A man has an 8% chance of developing prostate cancer and a 3% chance of dying from it. Indeed, it seems almost inevitable that, if one lives long enough, prostate cancer will occur. However, this does not mean that all men will be aware of the cancer, need any treatment, or even die because of the disease.

Why does Prostate Cancer occur?

The real answer to this question is not known. Nevertheless, here are a number of factors that can increase the chance of developing prostate cancer. Relatives of patients with prostate cancer have an increased risk of developing the disease themselves, especially if their father or brother were affected. There also appears to be a link with people living in urban areas exposed to pollution and those consuming large quantity of dietary fat.

What are the symptoms of Prostate Cancer?

There are often no symptoms associated with early stage prostate cancer. As the disease progresses and the tumour enlarges, it may press on the urethra, which runs through the gland and obstruct the flow of urine during urination. In this situation, the patient may notice a weak, interrupted stream of urine that requires much straining, and on completion he may sill feel that the bladder is not empty. However, these symptoms are not specific to prostate cancer and are most commonly found in benign (non-cancerous) enlargements of the gland.

Blood in the semen may be a sign of prostate cancer, although again this is a common finding and not normally related to malignancy. If the tumour is spread to the bones, it may cause pain. The spine is the most common site for this to occur.

What treats prostate cancer patients?

This is the job of a specialist doctor, an Urologist. Usually following an examination by the patient's General Physician refers the patient to the Urologist so that a full range of tests can be carried out and an assessment of the tumour made.

How is prostate cancer diagnosed?

The doctor will initially ask the patient questions to check their general medical health and see If they are experiencing any symptoms associated with prostate cancer. Having made a general examination, the doctor will then need to perform a rectal examination to the feel of gland. A gloved, lubricated finger is inserted into the rectum to check the size and the shape of the prostate gland.

Blood Test

The prostate can be evaluated by testing for the level of a particular protein in the blood called PSA (Prostate Specific Antigen). Prostate enlargement tends to cause an increase in the level of PSA, with malignant tumours producing a greater increase than benign enlargements. However, other conditions can also cause PSA to rise, such as a urinary infection. Therefore, although a slight elevation in the PSA may indicate prostate cancer. But it is by no means definite.

Ultrasound Examination and Biopsy

The Prostate can be imaged with ultrasound, a device often used to scan pregnant women. To visualize the prostate, a well lubricated probe, similar in size to a finger, is inserted into the rectum, and images of the prostate appear on a screen. The technique also provides pictures of seminal vesicles and the tissues surrounding the gland. The images produced help to identify areas within the gland that may be malignant, but the only way to prove there is cancer present is to take a biopsy. A small piece of tissue obtained by a special needle.

If a biopsy is to be performed at the time of the ultrasound scan, the patient will be forewarned. A small needle is inserted alongside the ultrasound probe, which can be moved to the area of the gland in question. The procedure is no more painful than giving blood, but may occasionally cause a momentary shooting pain in the base of the penis. The doctor will usually give the patient an antibiotic to help prevent any infection occurring.

Between 2-6 biopsies are normally taken, which are then analysed in the laboratory and a diagnosis obtained. After the procedure, it is quite common for the patient to see some blood in his urine, semen and stools, but this usually settles over a week or two.

Other Tests

Two other types of scanning machines are available. A computer tomography (CT) scan or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan are sometimes used to obtain pictures of the prostate and the surrounding tissue. Both are painless. The CT scanner uses X-Rays and MRI uses magnetic fields to produce their images.

Stages and Grade of Prostate Cancer

1. The earliest stage, where the cancer is so small that it cannot be felt on rectal examination, but is discovered in a prostate biopsy, or in a prostate tissue that has been surgically removed to unblock the flow of urine (as is a transurethral resection of the prostate - TURP).

2. The tumour can now be felt on rectal examination, but is still confined to the prostate gland and has not spread.

3. The tumour has spread outside the gland and may have invaded the seminal vesicles.

4. The tumour has spread to involve other surrounding tissues such as rectum, bladder or muscles of the pelvis.

Bone Scan

Once a diagnosis of prostate cancer has been made, if spread is suspected usually by the level of PSA, a bone scan can be used to see if the tumour has invaded bone. For this painless test, a tiny, harmless quantity of radioactive agent is injected into a vein. This makes its way to any cancer deposits within the skeleton and sticks to them. After a few hours, the patient is scanned by a special camera, similar to an X-ray machine, which detects these deposits, if present.

How is prostate cancer treated?

At present, there is no definite evidence as to which is the best treatment for prostate cancer, especially for early stage 1 or 2 tumours, and different urologists may have differing views. One of the reasons for this is that many patients with early stage disease will often live 10 years or more if no treatment at all is used - therefore, more involved therapies have a hard act to beat. However, in other patients, the disease can be much more serious. Unfortunately, whilst it is possible to give broad figures, it can be difficult to predict what course the prostate cancer will take in any individual.

Also, the side effects of treatment, which can be severe, must be balanced against the overall benefit of therapy. For example, there is little point in undergoing major surgery to take out the prostate if the tumour has spread to areas where it cannot be removed.

The treatment of prostate cancer is determined by the stage and, to a lesser extent, the grade of the disease. There are a number of treatment options for every stage, each with their own advantages and disadvantages. Thus, the therapy needs to be tailored to suit each individual patient. It is possible to cure patients with prostate cancer at an early stage, but even if cure is not a possibility, the disease can normally be kept in check for a number of years.

What are the treatment options in prostate cancer?

The different treatment options available to patients diagnosed with prostate cancer are described below. It is important that any patient with such a diagnosis is aware of the different treatments, and they should feel free to discuss these with their Urologist. Whatever therapy is undertaken the patient will need regular follow-up examinations, which may involve a PSA blood test and scans or x-rays, for a number of years.

Careful Surveillance

If the cancer has been discovered accidentally, during an operation to remove prostatic tissue blocking the urinary stream, or by a PSA blood test and biopsy, and the patient has no symptoms, "wait and see" policy may be chosen. This does not mean, "do nothing", but the patient will be regularly monitored by the doctor and if problems develop, appropriate action taken. These actions will often involve the use of hormone therapy, and on such a regime patients commonly live for many years. This choice is most frequently made by those patients with low grade disease specially if elderly.

Prostatic Surgery

A radial prostatectomy is an operation to remove the entire prostate and seminal vesicles. This operation can be performed through an incision in the lower abdomen or through an incision made between the anus and scrotum.

These are complex and major operations that usually require a hospital stay about one week. Such procedures should mot be confused with conventional prostate tissue blocking the urinary flow is removed, leaving part of the gland behind.

The advantage of surgery is that it is one off procedure and provided the cancer is confined to the prostate, will hopefully cure the disease. It avoids side effects of radiotherapy and is thought by some to be the most effective form of treatment for early prostatic cancer.

However, these are risks associated with radical prostatectomy. It is a major operation, and involves a number of week's convalescence to make a full recovery. Unfortunately, the prostate lies very close to both the sphincters that control urinary continence and the nerves that produce penile erection. In the past, removal of the gland often caused damage to these structures, resulting in postoperative urinary incontinence and impotence. Newer surgical techniques have reduced the occurrence of impotence, and severe incontinence is now uncommon. Furthermore, there are a number of new therapies to treat such side effects, should they occur.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy involves high energy easy at tumour, which aims to destroy the cancerous cells and leave the healthy ones intact. It is a painless procedure, like having an X-ray, although there can be troublesome aide effects associated with the treatment. It may be used in two situations:

1. to treat early cancers confined to the gland or the surrounding tissues and

2. to treat tumours that have spread to the bone and which are causing pain. Radical radiotherapy for a tumour localized to the prostate may be given in two ways. Conventionally, the rays are directed by a machine through the body into the prostate, as with an x-ray. The treatment is given on an out patient basis for five days a week for 4 - 6 weeks. However, when Radiotherapy is being used to treat the bones, only a few treatments are necessary.

Radiotherapy can also be given using radioactive seeds that are approximately half the size of a grain of rice. These seeds, typically 80-100 in number, are inserted through needles which are passed through the skin behind the scrotum and in front of the anus, then into the prostate. The procedure is performed under an anesthetic. It has the advantage of being either a day case or overnight stay procedure, with patients rapidly returning to normal activities.

The side effects of radiotherapy are normally limited to patients having radical treatment. But conventional radiotherapy is more lengthy than surgery and often causes tiredness, nausea, diarrhea, frequent and painful urination as well as bleeding both in the stools and urine, and local skin reactions.

The advantage of radical radiotherapy is that it can cure early prostate cancer without the need of a major surgery. It seldom causes loss of urinary control, and impotence is less common than with surgery.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is usually in tablet form, involves powerful drugs to attack the cancer cells and try to prevent them growing. It is a second line of defense for patient with advanced stage prostate cancer that is no longer controlled by hormonal therapy.

Hormone Therapy

When the cancer has spread beyond the prostate, going to either the lymph nodes or bones, hormonal therapy is effective at shrinking the tumour, and reducing the side effects of the disease. It does not provide a cure, but may keep the cancer in check for a number of years.

The prostate gland and prostate cancer are under the influence of testosterone, the male sex hormone, which drives the tumour to grow and spread. By blocking the body's production of testosterone or blocking its action, the growth of the tumour may be greatly reduced. There are number of techniques to administer such hormonal therapy. But whatever technique is chosen, certain side effects are common, such as hot flushes, a loss of sexual desire, impotence and occasionally breast tenderness or rarely enlargement.

Surgery

The parts of the testicles that produce testosterone may be surgically removed by a small operation, called "Orchidectomy" that can be performed as a day case procedure. This has the advantage of being a one off treatment that does not rely on the patients remembering their medication and tends to cause less breast problems. However, the operation is irreversible and men develop a high pitched voice after such a procedure.

Injection Therapy

An injection known as an "LHRH Analogue" is given once a month or every three months and this has a similar effect to removing testicles, but is reversible and does not involve surgery. Immediately after this therapy medication is prescribed to avoid the side effects.

Antiandrogen Tablets

This therapy involves taking daily tablets to block the action of testosterone. The drugs have dual action -

(1) they reduce the production of testosterone by the testicles

(2) avoid side effects like hot flushes, breast tenderness and impotence. However, Antiandrogen tablets can cause nausea and diarrhea.